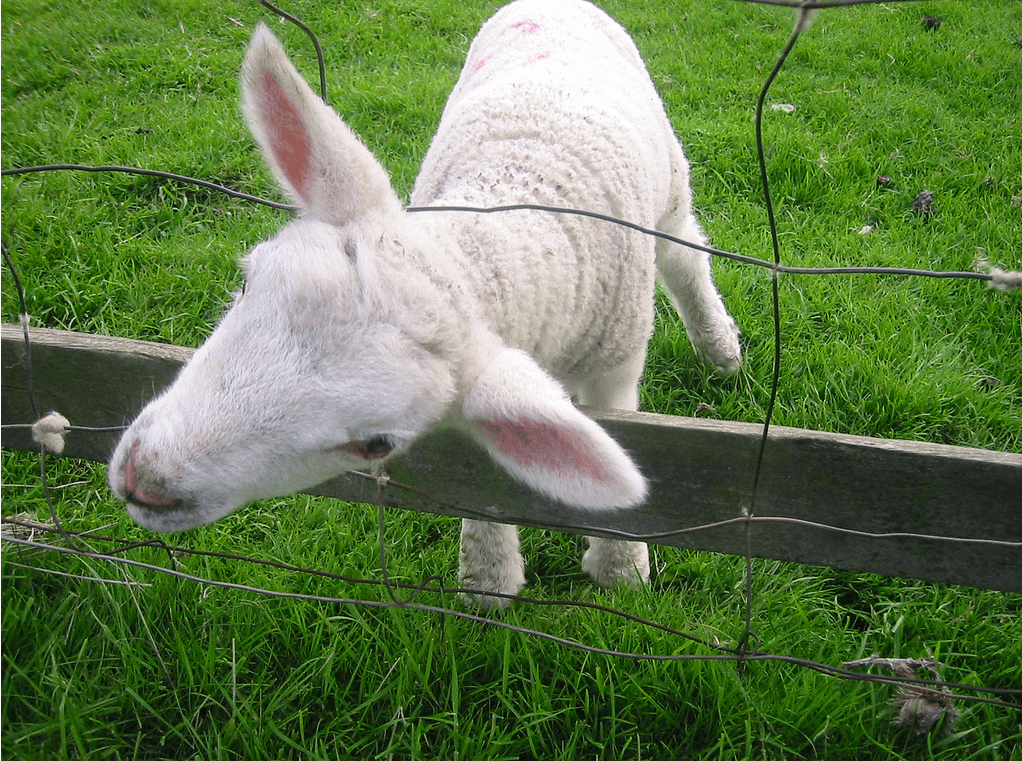

I grew up on a small family farm. Every day I would walk out behind our house to the pasture and feed the sheep. A long fence separated one side of the pasture from the other. The sheep always tried to eat the grass on the other side of the fence since there wasn’t much grass on their side of the fence. Now sheep being the silly critters they are, would often force their heads through the wire fence to graze on the few blades of grass within their reach, eventually getting their head stuck.

As a young boy, it was my duty to get them untangled from the ridiculous predicament which they had gotten themselves into. For my valiant effort I was often kicked and to make matters worse the little bugger never once came and thanked me afterward; he would just run off. Quite often I would come out the next day and the same dumb sheep would be stuck in the same hole in the same fence. As you can imagine, I wasn’t overly fond of the sheep, but I still found myself doing the same thing each day hoping for some recognition from the sheep and getting none. I learned a valuable lesson about people from that experience. Let me explain.

There’s an easy to understand psychological model called the Drama Triangle created by Stephen Karpman, M.D in 1968. This model explains the different roles people play within a type of enabling dynamic or social game. There are three roles, the Victim, the Persecutor and the Rescuer. The Drama Triangle typically begins with someone playing the victim. The victim then identifies an entity or person as the persecutor and then quickly looks for someone to play the part of rescuer who will rescue them from the persecutor. This enabling dynamic or social game is not always apparent to the participants. Many of us play these different roles with different people unconsciously.

If we take a sheep and place it in the role of the “Victim” and place me in the role of the “Rescuer”, that is a perfect explanation of the typical results that come about when a “Rescuer” and “Victim” dynamic exists between people. Now, I’m not going to try to stretch this analogy far, I’m only going to point out a few similarities between my situation with the sheep and the enabling behaviors we often see between people.

In attempting to rescue a helpless critter, I often put myself in harms way. When someone in the victim mentality acts helpless and invites a rescuer to “save” them, it is the rescuer who most often gets kicked or hurt in the attempt.

The sheep were ungrateful. Likewise, a “Victim” is usually entitled or unappreciative of the help they receive, they just expect it as part of their due.

Like the sheep who got stuck the very next day (and sometimes the very same day) “the Victim” is in constant need of rescuing because their behavior doesn’t change.

Now, unlike the sheep in the experience of my youth, people can learn how to untangle themselves from the holes they put themselves into. Here is my caveat: Victims don’t have a reason to learn how to pull themselves out of the holes they get into, if a rescuer is always willing to do that for them. There are ways we can help people who put themselves in the victim role without enabling them. But we cannot constantly pull them out of the holes they repeatedly put themselves into and expect them to learn from it and change. If we want people to be motivated to learn how to get out of holes on their own and to avoid getting into holes in the first place, we must be willing to watch them struggle and work and sweat a bit. When these people are ready to come to us and ask for guidance and trust the answers we give them, that’s when our influence is of genuine use to them. But, if we “help” them by jumping in before they have even acknowledged that they need help, we hurt them and we hurt ourselves in the process. Remember my sheep analogy: Unless they can learn to get their head out of the fence for themselves, they will just end up stuck in the fence tomorrow.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Eric Hatton has spent most of the last six years working as a field staff in wilderness therapy where he coached students on primitive fire skills, making and setting traps and other important wilderness skills. He also coached staff as they learned leadership skills and as they learned to disrupt dysfunctional behavior in the students. Eric loves brainstorming with people. He loves to help people organize their thoughts and change their dreams and desires into tangible, achievable goals. He loves to help people to discover their passions and to help them find ways to use their passions to realize their goals. He is passionate about building great teams and organizations and helping others succeed.